DO THE WORK

Beneficial Fire

Pile burning and broadcast burning are the two main types of beneficial fires. Pile Burning generally consists of individual, small brush pile fires. Prescribed fires and Indigenous cultural fires are often referred to as broadcast burns when they cover more than an acre and “broadcast” fire across the land. There are differences between Indigenous cultural fire and prescribed fire, but this guide uses the term beneficial fire to cover both.

The Mediterranean climate of Sonoma County creates a fire-prone environment. Wet winters promote vegetation growth and long rainless summers dry these plants out, turning many areas into tinderboxes of flammable material. Before Europeans arrived, between 4.5 million to 12 million acres of California burned every year—up to an eighth of the state. These were started by a combination of lightning and Indigenous people who strategically utilize fire to promote biodiversity, cultural resources, and to prevent destructive fires.

Before Europeans settled what is now California, fire was common except in deserts and at elevations above 6,000 feet. Some ecologists estimate that fire helped to shape three-fourths of California’s vegetation. Native plants are adapted to fire. For example, coast live oak and redwood can survive a fire even when heavily charred. Native, perennial bunchgrasses (such California oatgrass and purple needlegrass) have roots that can grow as deep as 20 feet that allow them to regrow quickly after a fire. Bishop pines and several “fire follower” wildflowers have seeds that cannot germinate without fire. Practitioners in Sonoma County have seen that deciduous oaks (blue, black, valley, and Oregon white oaks) are less heat-tolerant than evergreen (“live”) oaks, though more heat-tolerant than thin-barked trees like bay laurel or madrone. Those trees’ adaptation to fire is to vigorously resprout from their roots.

With European arrival, the United States and California governments pushed Indigenous people into reservations, seized their land, forbade Indigenous burning, and instituted an aggressive fire suppression policy. This contributed to overcrowded forests throughout the West. Many scientists link fire suppression to an increase in the severity of wildfires, furthering the impacts of climate change and the accumulation of fuels. One study found that severe fires, in which a conflagration kills 75 to 100 percent of the trees, are larger and occur more frequently in California than at any time in recorded history.

Local Professional Asa Voight presents at the Living with Fire: Sonoma County Forest Conservation Conference, Sonoma County, 2023. sonomaforests.org/conference/

Benefits

Beneficial fire brings many benefits, including:

- Reducing risk from wildfire by reducing fuel loads: “Beneficial fire practices—which include prescribed, cultural burning, and managed fire—are essential to reduce the risk of large-scale catastrophic fire in California.” (CAL FIRE)

- Removing accumulated fuels on the ground including wood, duff, and thatch

- Recycling nutrients back into soil

- Creating beneficial “mosaics” – patches of different types of plants – that offer more space and resources for a broader spectrum of plants and animals to flourish

- Significantly increasing streamflow

- Promoting specific native plants and wildlife habitat

- Reducing pests and diseases

- Reducing some invasive weeds, but only if done correctly. Improper implementation can increase invasive species.

- A variety of ecological and cultural purposes when practiced by Indigenous communities

Several ecological benefits can only be achieved, or are best achieved, with the use of beneficial fire, including:

- Reduction in pests and pathogens

- Regeneration of fire-dependent trees and plants

- Promoting healthy soil

- Killing or inhibiting certain common invasive plant species

“Fire has long been an important management tool in California. Native Americans were early innovators with fire, using it for millennia to cultivate basketry supplies, food resources, and other cultural necessities, and to maintain open forests and woodlands to facilitate travel and communication. Ranchers also used fire to maintain habitat for wildlife and domestic livestock, and in more recent decades, its uses have grown to include fuels reduction, invasive species control, and ecological restoration. Prescribed fire, or the use of fire under predetermined conditions to achieve specific objectives, is now well-recognized as one of the most versatile and cost-effective tools available, with utility for many different kinds of California land managers, from private ranchers and forestland stewards to tribes to staff on national parks, forests, and wildlife refuges.” UCCE

Beneficial fire is increasingly popular, but still faces some barriers such as cost and occasional public backlash. Given these obstacles, some public and private land managers, especially near urban areas, opt to thin without burning, typically followed by chipping or mastication. While some studies show that such methods alone can increase wildfire resiliency, most research and field experience indicates that thinning coupled with beneficial fire is the most effective. Thinning without fire cannot deliver such ecological benefits as regeneration of fire-resilient trees and plants and promoting soil health.

Smoke can ruin wine grapes if it is of a certain concentration, duration, and timing. Timing beneficial fires to occur before sugars develop in nearby wine grapes (roughly early July) is an interim strategy, while the science gets worked out regarding “smoke taint.”

Beneficial fire can reduce the severity of subsequent wildfire. The right side of the photo is an area burned intentionally in 2019 at Monan’s Rill in northeastern Sonoma County. Surface fuels were consumed by the burn. The left side has just burned in the 2020 Glass Fire. The Glass Fire stopped at the edge of the prescribed burn, because there was not enough fuel to carry it. Photo: Chris Schaefer

When and Where to Implement Beneficial Fire

Beneficial fire may be appropriate in many areas of Sonoma County, such as:

- Places that lack diversity in species richness or spatial structure, where invasive species are present or increasing

- Areas with excess fuel loads, meaning excess thatch, duff, dead plants, or ladder fuels (thick undergrowth or lower branches that allow fires to climb into canopies)

- Areas that are being encroached upon by woody plant species, such as Douglas fir encroaching into oak woodlands or coyote brush encroaching into prairies

- Previously managed areas that need maintenance, such as in shaded fuel breaks or along roads

Key Points Before Proceeding

Different vegetation communities have different optimal fire frequencies, or “fire return intervals.” If sites burn too frequently or too rarely, their health declines. For example, too-frequent fires in chaparral can convert biodiverse shrublands to low-diversity grasslands with mostly non-native, short-lived, flammable grasses. Assuming that ecosystem health was greater before European settlement, it’s helpful to know the fire return intervals in different vegetation communities during Indigenous stewardship. This data can inform (not dictate) long-term targets for land stewardship.

Sources: Adapted from Table 2, A Summary of Fire Frequency Estimates for California Vegetation before Euro-American Settlement. *Adapted from Short Fire Intervals Recorded By Redwoods at Annadel State Park, California. Confidence in estimates for chaparral is less than other vegetation communities. **Adapted from Distribution and frequency of wildfire in California riparian ecosystems.

Putting fire on the land is a big step, especially where it has been absent for decades or centuries. It is critical to consult with professionals, Indigenous fire practitioners, and CAL FIRE or local fire agencies.

If you want to elevate the Indigenous benefits of intentional fire, the right approach is to build a relationship with an Indigenous person or group and ask them, how can I be of service, how can this land be of service? Offer to compensate them for their time. Explain to them how much leadership and control cultural fire practitioners will have over the burn. To explore options for cultural or Indigenous fire on private land, try Hybrid Indigenous Stewardship or the California Indian Basketweavers’ Association, and see the links to tribes at the bottom of the homepage, and learn about Indigenous land gardening.

Excellent resources that provide education or support with planning, including burn and air quality permits, include:

- The Fire Forward program can provide on-site support, and has a comprehensive training program. Learn if prescribed fire is a fit for your project by filling out this interest form. Get an idea of costs from this 2023 guide from Fire Forward and Regenerative Forest Solutions.

- CAL FIRE staff and your local fire department.

- Contact a UCCE Fire Science Advisor to learn more about local burn initiatives.

- Get help with a beneficial fire from the trained volunteers at the Good Fire Alliance, our local prescribed burn association. Learn about Working with Prescribed Burn Associations.

This page about liability for prescribed fire has resources about legal responsibilities and insurance for people who want to enact it on the land.

Costs for a beneficial fire can range from $5,000 to over $50,000. Factors affecting cost include how steep the terrain is, whether there are barriers inside the burn unit such as fences or canyons, how dense the woody vegetation is, how much site preparation is needed, how many fuel types are present, whether control lines must be created, and proximity to buildings or infrastructure.

As described at Monan’s Rill above, beneficial fire (particularly when combined with Thinning and other vegetation management), can produce dramatic results. Here aerial photography shows how different treatments moderated the impact of Oregon’s 2021 Bootleg Wildfire.

Permits are required for beneficial fires. Visit Sonoma County Fire District and Permit Sonoma to learn more. This CAL FIRE website has a decision tree for which burn permit is necessary for the burning you wish to do.

How to Burn

It is not recommended to attempt any beneficial fire without assistance from experienced professionals or Indigenous fire practitioners. This section provides high-level guidance for broadcast burns; not detailed implementation instructions. (For burning small brush piles, see Pile Burning.)

- Beneficial fire is a long-term stewardship practice. Work toward a long-term plan for ongoing broadcast burns, based on a fire frequency that fits the onsite vegetation communities and your stewardship goals.

- Consult with experts to plan and supervise the burn. People looking to burn need to be clear on the burn’s purposes, preparation, permitting, liability needs, notifications, resources, labor, timing, location(s), and the frequency of ongoing maintenance burns.

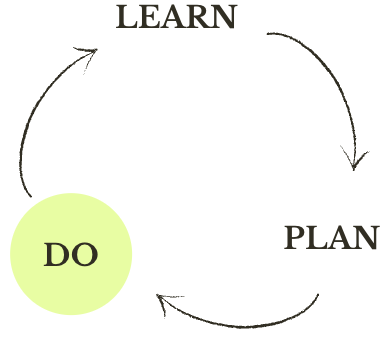

- A beneficial fire involves these steps: planning, permitting, site prep, the burn itself, and mop-up. Planning can take months depending on site complexity and prep requirements. Permitting can take up to a month. For example, air quality approvals are granted only upon review of a highly detailed smoke management plan about a month before the burn date. CALFIRE burn permits are issued after reviewed after review of a detailed burn plan about two weeks before the burn date.

- Some sites will require extensive preparation before broadcast burning. The main item in site prep is Thinning and/or Limbing along control lines. Control lines are linear areas with virtually no fuel (such as dirt roads or scraped boundaries) around the burn unit prior to burning. Keep in mind that one of the main effects and benefits of the burn is to thin the understory, so it’s not necessary to thin inside the burn unit, at least not before getting input from a professional. On some sites such as grasslands or where animals have grazed, site prep might be minimal.

- Notify neighbors, fire agencies, local news outlets, and local governments about the upcoming burn, including its purposes. This helps normalize beneficial fire and reduce fears of wildfire.

- Planned burns can be canceled up to the day of the burn, if the weather does not match the conditions laid out in the permit(s). Communication needs to reflect this reality. You may want to build a backup day into your plan from the outset.

Variations on this Practice

The amount of thinning and removal of woody material before a first burn can vary enormously. Some beneficial fires require extensive vegetation management, while others don’t require any. For example, “first-entry” broadcast burns are done without any prior vegetation management except for control lines. On other sites, where fuel loads are very high, or near dense housing, or if there are high-value trees or heat-sensitive animals, several years of extensive thinning–often followed by pile burning–may be needed before broadcast burns can take place.

Timing Considerations

- Beneficial fires are expected to occur during a window of time, rather than a specific date, since weather is unpredictable. To choose the time window, consider factors such as weather, air quality, permitting, insurance, effectiveness based on the ecological sensitivities of target species, and availability of personnel and resources that can be assigned at the last minute to wildfires.

- Pile Burning season typically lasts between November 1 to May 1.

- Broadcast burning can occur any time of year, depending on whether the goals are controlling invasive species, improving forage, overall biodiversity, reducing fuels, or some combination. Hotter burns can be achieved during summer. When a burn is meant to reduce the presence of an invasive weed, remove encroaching Douglas fir, or promote particular desired native species, burn timing should be influenced by those species’ particular biological windows. For example, early-season burns can be very effective at reducing medusahead, an invasive grass, while later-season burns are usually best for increasing overall grassland biodiversity.

- Time elapsed since the last fire is an important consideration, as it influences the successional stage of the landscape.

- The timing for a broadcast burn should weigh the impacts on nesting birds. See guidance on surveying and avoiding nesting birds.

Equipment

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

- Long pants and a long sleeve shirt made of fire retardant or natural materials (i.e. Nomex, cotton, wool)

- Fire certified boots

- Helmet

- Eye protection

- Leather gloves

- Ear protection

Tools

- Water backpacks

- Water tenders

- Hoses

- Drip torches and other lighting implements

- McLeods

- Rakes

- Shovels

- Wire cutters for areas with fences

Maintenance

Beneficial fire is a long-term stewardship practice. From the beginning, an ongoing approximate schedule of repeated burns should be planned for, based on the best available estimates of the fire frequency that will achieve land management goals in the vegetation communities on site. Building relationships with the Good Fire Alliance, Fire Forward, UC Extension, Indigenous burning groups, and local fire agencies may help bring in assistance and funding over time.

Related Practices

Retaining and Creating Habitat Features

Please note: this is a general guide. The specifics of how and when to do this practice will depend on many factors, including the site’s particular vegetation, climate and topography, history, and land management goals. Always consult a professional if you’re unsure.

Do you have your principles in mind? Remember to regularly check in with your land management goals, to assure your practices and actions will actually achieve them.

Additional Resources

- The best practical guide is Fire Forward’s Guide for Land Managers

- UCCE Prescribed Fire page, Forestry Advisor and Fire Advisor

- The Good Fire Alliance, Sonoma County’s Prescribed Burn Association

- Sonoma County Regional Parks prescribed fire information

- California Fire Science Consortium, to learn more about fire in California.

- The Nature Conservancy’s “frequently asked questions” page about prescribed fire

- Reuters article describes the need for prescribed fire in Sonoma County (2023)

- Press Democrat article about Indigenous burning in Sonoma County (2021)

- Grist article reviews research on the benefits of fire and highlights present Indigenous fire stewardship in Sonoma County (2022)

- Excellent story and interactive maps about Sonoma County’s 2017 fires from Sonoma County Ag + Open Space

- Save the Redwoods League page on redwoods, their history with fire, and stewardship needs

- Track efforts to provide more liability protection for land managers; see this CAL FIRE page

- Adapting western North American forests to climate change and wildfires: 10 common questions summarizes peer-reviewed research on the benefits of prescribed fire.

- California Indians and Their Environment and Tending the Wild are groundbreaking books documenting Indigenous stewardship practices, including cultural fires, in what is now California.

- Fire Tender is a documentary about Yurok women fire practitioners working to return Indigenous fire and tribal sovereignty to the land. INHABITANTS is a film with associated webinars, about Karuk and Yurok fire.