DO THE WORK

Targeted Grazing

Targeted grazing is the use of livestock grazing or browsing at a specific season, duration, and intensity to achieve landscape management goals. It is also called prescribed grazing, managed grazing, or prescribed herbivory.

Photo: Bureau of Land Management.

Benefits

Grazing animals (sheep, cows, goats, etc.) can reduce low-lying fuels such as grasses and shrubs, and can boost the ecological health of the land.

Grazing:

- Reduces wildfire severity by removing light, flashy fuels

- Increases disturbance, which then promotes growth by native grasses, shrubs, and trees

- Fosters biodiversity by opening pockets of soil where native seeds can germinate and removing invasive and non-native species, especially in grasslands that are mostly non-native short-lived grass species

- Improves forage and accessibility for wildlife as well as humans

When & Where to Implement Grazing

Grazing animals can be used to reduce excessive fuels in locations where there is adequate infrastructure, support, and water, especially areas with sloping terrain where other methods are less practical. Grazing is often used in areas with excessive shrub or grass growth, especially where layers of thatch (inedible dried grass from previous seasons) have built up. Grazing can be particularly helpful in shaded fuel breaks, along roads, or in the defensible space zone around structures.

If a grassland has not been grazed for a long time, the plants can be old, not appealing to grazers, or not nutritious. Often, contract grazing services are hired when forage quality is not ideal, and when labor costs required to launch grazing is potentially prohibitive. It can take from one to three years of managed grazing to improve forage quality, biodiversity, the return of native species, etc. Fire can greatly improve forage quality, so targeted grazing can be a good follow-up to prescribed burning or wildfire.

Targeted grazing may not be a good practice in certain situations:

- On steep sites, especially with loose soil, where animal hooves will cause erosion and soil loss

- During times of year when sensitive plant or animal species are reproducing or vulnerable to disturbance, such as flowering time for rare annual plant species

- Where fences or other containment systems are likely to fail

- Where it is not physically or economically feasible to control the duration or extent of grazing. For example, areas with thick brush are difficult and labor intensive to fence.

- Where water sources for grazing animals are not available

- Where predation pressure is high and guard animals are not available

- Where there is insufficient grass or browse to sustain animals, such as in some shady forests with little ground-level vegetation

The foreground shows evidence of overgrazing, with bare soil and uprooted grasses. In the background, the cattle are in a waterway that is not fenced, and likely polluting it with feces.

Photo: Los Padres ForestWatch.

Key Points Before Proceeding

Without proper management, grazing can be a negative instead of a positive. Poorly managed grazing can introduce invasive species, damage sensitive habitats, degrade soil and cause erosion, foul streams, and stress native species. To avoid overgrazing, it is essential to:

- Use a site-appropriate number of animals for a site-appropriate amount of time

- Graze at the correct time of year

- Keep animals out of riparian areas, streams, and other sensitive areas

- Providing independent water sources away from streams and wetlands

To dial in your grazing effort and get the results you seek, get training or guidance from a professional rangeland manager, natural resource manager, or local grazing professional.

“The species of livestock best suited for the specific vegetation management goals depends on both the plant species of concern and the production setting.” From UCCE Grazing School:

Cows

“Cattle have large rumens that are well adapted to ferment fibrous material and are classified as grass and roughage eaters. They are therefore generally superior to goats or sheep to manage fibrous herbaceous vegetation such as dormant grasses.”

Sheep

“Sheep are generally considered an excellent species to control herbaceous weeds. Sheep have a narrow muzzle and a relatively large rumen per unit body mass. These allow them to selectively graze and yet tolerate high fiber content, and result in diets generally dominated by forbs [broadleaf plants, like clovers and wildflowers]. Sheep are also small, sure-footed, and well suited for travel in rough topography that may not be easily accessible for chemical weed control.”

Goats

“Goats have narrow strong mouths well designed for stripping individual leaves from woody stems and for chewing branches. Goats also have a large liver mass relative to cattle or sheep and may therefore more efficiently process plants that contain [natural chemicals, such as] tannins or terpenes.”

Mixed herds

“Using a mixed herd can provide added benefits as the combination of species consumes a wider range of plant species. Using cattle with sheep or goats could also provide predator protection to the more vulnerable species. Otherwise, a guarding animal, usually a dog, is kept with the grazing herd.”

Many contract grazers provide all necessary equipment (temporary fences, buckets, water, supplemental food, etc.) as part of their fees, although it is not unusual for water to be provided by the land manager.

Fencing to contain livestock is required by law to keep animals in their grazing areas and comes in all shapes and sizes:

- Permanent – Perimeter fencing, generally made of wood or metal and sized based on the animals it contains. Consider wildlife friendly fencing, for example, when installing fencing for larger species such as cows, using smooth wire for the bottom strand allows movement of wild grazers, such as deer, through the area.

- Temporary – Temporary fencing is usually electrified to keep grazing animals in smaller areas for a short graze period. The land is grazed and then rested, allowing for regrowth. The fences are moved frequently.

How to Implement Targeted Grazing

There are many variables to consider when designing a grazing approach: species, number, timing, duration, planning subareas, and more. To dial in your grazing effort and get the results you seek, get training or guidance from a professional rangeland manager, natural resource manager, or local grazing professional.

Timing Considerations

Grazing needs to be timed carefully in order to attain good results.

For annual plants, grazing before seeds are produced reduces the number of seeds available to germinate the following season. Unwanted grass and species can be grazed early and often in the growing season to reduce seed production, while valued annual plants should be allowed to seed before they are grazed.

For perennial plants (plants that come back from the same roots each year, including perennial grasses, wildflowers, trees, and shrubs) repeated grazing removes the leaves from the plant, depleting the energy stored in the roots. Perennials are most damaged by grazing just after the plants start growing each year. Therefore, graze unwanted perennial species early in the season to reduce their vigor; graze valued species, if at all, later in the season on a rotating basis.

In grasslands that have both native perennial grasses and non-native annual grasses (a very common situation in Sonoma County), the timing of grazing is critical. Invasive annual grasses start growing earlier in the spring, and they grow faster than perennial grasses, generally out-competing native perennial grasses unless managed. These grasslands should be grazed early in the growing season, before perennial grasses and forbs begin to grow. As native perennials begin to grow, remove the animals or rotate them through pastures to allow perennials to flourish. After they have established, perennial plants can be grazed seasonally, considering rainfall and temperatures.

Equipment

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

- Long pants

- A long sleeve shirt

- Sunscreen

- Boots

- Leather gloves

Maintenance

The need for maintenance grazing is based on the habitat, use of the land, and desired goals. Graze more frequently where the plants grow faster, such as in grasslands or open woodlands, less frequently where slopes are steep or natural resources are more sensitive. The grazing plan you develop with a professional who understands your set of land stewardship goals clearly should provide you with a multi-year roadmap.

To avoid overgrazing, or excessive grazing in one area that leads to a decline in the health of that area, use rotational grazing. Rotational grazing is the regular shifting of grazing animals to different grazing locations to allow areas to rest.

Related Practices

Retaining & Creating Habitat Features

Managing Roads and Trails (coming soon)

Please note: this is a general guide. The specifics of how and when to do this practice will depend on many factors, including the site’s particular vegetation, climate and topography, history, and land management goals. Always consult with a professional if you’re unsure.

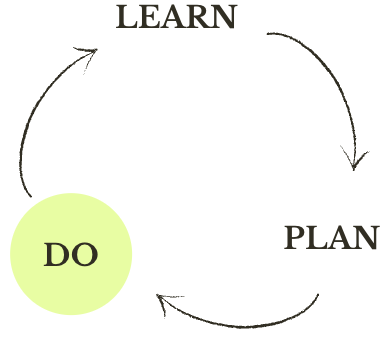

Do you have your principles in mind? Remember to regularly check in with your land management goals, to assure your practices and actions will actually achieve them.

Additional Resources

LandSmart Grazing Program from Gold Ridge Resource Conservation District

Grazing Professionals for Hire around Sonoma County

Match.Graze, which connects people who have land that needs grazing with people who have animals ready to travel and graze

Grazing resources from UCCE