DO THE WORK

Managing Woody Species Encroachment

Encroachment by woody species occurs when trees or shrub species gradually grow into other vegetation communities. In Sonoma County, encroachment often occurs when Douglas fir or California bay trees grow in forested or chaparral areas, or manzanita species and coyote brush growing into grassy areas. Encroachment occurs where there is a lack of beneficial disturbance over time, which allows unfettered ecological succession. Beneficial disturbances include Beneficial Fire, flooding, and Indigenous or non-Indigenous land stewardship activities

Before (left) and after (right) managing woody species encroachment in a native grassland. Photo: Eric Schoohs.

Benefits

Woody species encroachment increases the likelihood of high-severity fire, decreases forage and habitat for wildlife, decreases biodiversity, and inhibits ecosystem services.

Managing encroachment promotes native California vegetation communities such as perennial grasslands, chaparral, and oak woodlands that offer carbon storage, forage for animals, water retention, soil protection, and fire resilience as part of a fire-adapted landscape. It allows light to penetrate to the ground surface, which then allows a diversity of plant species to germinate. In Sonoma County, if woody species encroachment is not managed, many forested areas would eventually become dark, low-diversity Douglas fir or California bay forests, and many grasslands and chaparral areas would convert to forest and disappear.

Conditions that call for this practice

Encroaching woody species should be managed wherever desirable vegetation appropriate to the specific ecosystem is being overcrowded or over-topped by encroaching species.

Key Points Before Proceeding

Succession and disturbance work in tandem to maintain balance in an ecosystem. Succession allows the development of mature habitats and “old growth” organisms. Disturbance, ideally periodic and patchy, makes space for young plants and more diverse species. Without disturbance, forests and other habitats will tend to fall apart, becoming less diverse, overcrowded, and more susceptible to fire, disease, and climate variations.

Understanding the history of the land is necessary to get it back to, or keep it on, a healthy and resilient trajectory. If an area was historically grassland and now it is mostly coyote brush, or if a mature oak woodland has been overtopped by dense growth of Douglas fir, managing the encroaching species is likely to be beneficial. Use the Land Inventory Template to help learn about, track, and analyze the land’s history.

The widespread encroachment of certain woody species into forests, chaparral, and grasslands in Sonoma County represents a significant change from the historical conditions of these habitats. Prior to our current era of fire suppression, many grasslands in Sonoma County were maintained by regular use of low-intensity fire, first by California Indians and later by ranchers. Regeneration of grassland, chaparral, and hardwood species in forests following wildfire may represent a return to more historically typical conditions. Renowned ethnobotanist M. Kat Anderson, author of Tending the Wild, notes that in some woodlands, Indigenous people removed fir seedlings and saplings by hand to prevent them encroaching on oaks and native grasslands.

Encroachment looks different in different vegetation communities:

Grasslands

Grassland can be filled in by the forest or shrubland surrounding it if disturbance does not occur to thin the area or push the encroachment back. The first species to encroach grassland are often coyote brush, manzanita, or live oak. Grassland can produce valuable old-growth heritage plants, just as forest can: California native perennial grasses can live over 100 years in good conditions, but can quickly die if covered by deep shade.

Shrubland

Tall, fast-growing, shade-tolerant tree species (often Douglas fir or California bay) can encroach into areas of chaparral (such as manzanita and toyon), increasing stem density and fuel loads, shading out established chaparral plants, and converting the area into forest. You may see single trees in the middle of shrubland, or the edge of the forest may shade out or crowd the chaparral.

Woodlands and Forests

Less dense woodlands, often with multiple co-dominant tree species (such as mixed madrone/oak forests), can be filled in by shade-tolerant species (often Douglas fir or California bay). You may see large numbers of young Douglas fir or California bay saplings starting to grow in a forest or woodland, and few or no young oaks or other hardwoods, and the forest may become difficult to walk through. These species create dense shade where there once was only dappled shade. Douglas fir seeds can germinate in the shade, but those of oaks, madrones, buckeyes, etc. need sunlight to germinate, so over time, without active stewardship, the shade-tolerant species will come to dominate.

Graphic depicting the phases of woody encroachment from the US Forest Service.

Read how Douglas fir encroachment affects the culturally essential acorn crop.

Learn how Douglas fir encroachment is managed at Occidental Arts and Ecology Center.

In Practice

How to Manage Woody Species Encroachment

In most situations, follow the Thinning and Limbing recommendations for fire resilience and ecological health. Wherever possible, work toward using Beneficial Fire at a frequency appropriate for the vegetation community, as this in tandem with regular maintenance activities is the best long-term practice for preventing and managing encroachment.

- The most efficient tactic is to prevent the problem from getting worse by removing the youngest plants encroaching into the area. Hand pull when possible. Removing saplings while they can still be pulled by hand can save time and money, and decrease the stress on the remaining trees by decreasing competition and increasing the amount of water available later into the dry season. If hand pulling is not an option, cut off the stems as close to ground level as possible.

- In encroached grasslands, remove some or all dense patches of shrubs. Consider leaving some shrub cover for wildlife habitat.

- Remove trees of the encroaching species (usually Douglas fir or California bay) that are smaller than 10 inch DBH and are acting as ladder fuels or shading out, or soon will be shading out, high-value native species such as mature oaks, madrones, perennial grasses, or shrubs. Remove trees by cutting them down (see Thinning) or, if they are too big, by girdling them.

- Consider retaining occasional large individual trees that provide wildlife habitat. For example, Douglas fir trees taller than anything around them are likely valuable perching and roosting sites for birds.

- Removal of trees above 10 inch DBH is hazardous; if larger trees are putting desirable shrubs or trees at risk, consult an arborist or forester about their removal. If encroaching trees are too big to cut, limb them up as high as possible to reduce fire risk and shading for adjacent plants you wish to retain.

- Consider marking the boundary of the area where you have removed encroaching plants, so you can see future encroachment more clearly.

Managing woody material

Leaving a lot of cut woody material in grasslands or in chaparral can damage native grasses and increase fire risk. Use these Practices to dispose of materials in less sensitive areas, such as on top of invasive plants, weedy shrubs, or in a forested area. Consider creating Wildlife Habitat Piles or Pile Burning. This protects areas where native grasses or young chaparral sprouts grow and removes competition without increasing the risk of fire.

An oak woodland before and after the removal of encroaching Douglas fir during the piercing phase at Pepperwood Preserve. Photos: Pepperwood.

Variations on this Practice

Managing encroaching woody plants is usually not an all-or-nothing proposition. Consider your goals, the habitat value of retaining certain plants, the speed of encroachment, and the amount of material you’re able to manage at one time. Rather than removing all encroaching trees or shrubs, you may retain select individual natives of value (e.g. manzanita in grasslands, or oak trees among native grasses) and thin around them to offer diversity, shade, and beauty in the landscape while still opening space for grasses and other important species .

Timing Considerations

- Any removal of larger shrubs or trees should be done outside bird nesting season, generally from March through August in Sonoma County. This timeframe covers the majority of songbirds and raptors (birds of prey). If vegetation management must be done during nesting season, see Nesting Bird Surveys.

- Manage flammable materials outside the fire season so they don’t pose a risk to you, your home, or your trees in case of a wildfire.

- Hand-pulling encroaching plants is easiest when the ground is moist or wet, but driving vehicles onto wet soils should be avoided at all costs.

- Encroachment happens little by little, and never stops, so pace your work. A general rule is: the taller a species is, the longer it takes to get fully encroached upon and shaded out, but the more work it is to remove the competition. Focus first on areas most valuable to you, or areas with the highest biodiversity.

Equipment

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

- Long pants

- Boots

- Helmet

- Eye protection

- Leather gloves

- Ear protection

Tools

- Hand saw

- Pruner

- Chainsaw and/or loppers

- Pole saw or ladder to use with hand tools

Maintenance

Encroachment can happen quickly. It’s important to walk the land regularly to ensure there is balance between the vegetation communities. Grasslands are the most vulnerable to encroachment, and should be inspected most often. In chaparral, an annual walk with a focus on trees growing among the shrubs or encroaching at the edges should suffice. Established forests take longer to be shaded out and require less regular maintenance, but annual inspections allow hand-pulling of seedlings, which is an easier form of maintenance.

Once cut, many woody species (other than conifers such as Douglas fir) are likely to resprout. How resprouts are managed depends on the desired outcome:

- Do you want this plant in this location?

- If no, remove all resprouts. For very vigorous resprouters like California bay or redwood, consider using herbicide if mechanical maintenance is not feasible.

- If the plant is acceptable in that location, then ask…

- Do dense resprouts pose a problem or risk for this particular location and warrant thinning?

- If no, then no action is needed.

- If yes, then for trees remove all but 2 or 3 of the tallest or most vigorous sprouts to accelerate upward growth. For shrubs, generally retaining all resprouts is fine.

- Do dense resprouts pose a problem or risk for this particular location and warrant thinning?

Related Practices

Retaining & Creating Habitat Features

Please note: this is a general guide. The specifics of how and when to do this practice will depend on many factors, including the site’s particular vegetation, climate and topography, history, and land management goals. Always consult with a professional if you’re unsure.

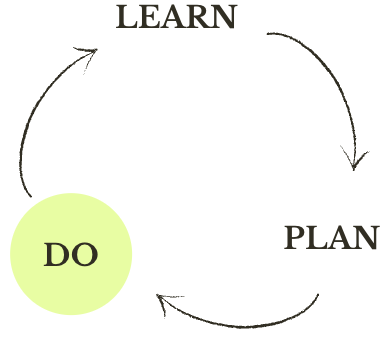

Do you have your principles in mind? Remember to regularly check in with your land management goals, to assure your practices and actions will actually achieve them.

Additional Resources

Article by local author Kristina Rizga discussing the historic use of fire in the region, the encroachment of Douglas fir, and the use of prescribed fire to help prevents wildfires in the West

Conifer encroachment in California Oak Woodlands, by UC Cooperative Extension