LEARN

A PRIMER ON ECOLOGICAL PRINCIPLES … or, HOW LAND WORKS

When you align your land stewardship activities with these fundamental principles, you’re more likely to choose actions that advance more than one objective at a time, and you’re more likely to achieve your goals.

Time

- Ecological processes function at many time scales–some long, some short. Ecosystems change through time.

- Our brains have a hard time understanding the long-term effects of rare disturbances such as big floods or wildfires, or processes that operate over periods longer than human life spans such as forest succession.

- Today is just a snapshot in the lifespan of any site. The ecological system you see is a consequence of historical events. Decisions made today affect options available in the future.

- The full effects of human activities are often not understood for decades or centuries. For example, changes that started in the early 1800s–such as short-lived grasses invading grasslands, or building logging roads–continue to affect whether water sinks into the soil or simply runs off the land.

Succession

Succession is the principle that over time, without disturbance, vegetation species and communities will shift in predictable ways. This shift typically favors more shade-tolerant species: grasslands will fill in with shrubs, shrubby areas will see trees establish, forests will get crowded by species like California bay laurel and Douglas fir. Depending on the plant community, succession may lead to “old-growth” conditions or it may lead to biodiversity loss and hazardous fuel accumulation. In both cases, periodic disturbance (fire, wind storms, disease) will provide a “re-set” of conditions to an earlier successional state and allow other species to establish. All successional states provide unique habitat for native plants and wildlife. There is not a single state that is a permanent, desired condition. Rather, land stewards recognize that there is a dynamic balance within landscapes between succession and disturbance, and that in many habitats a mosaic of successional states will tend to support biodiversity, resilience, and space for rare and endangered species to persist.

Disturbance

- Land is always changing; change is the only constant. The type, intensity, frequency, and duration of disturbance shape the land and the life it supports.

- Some disturbances are natural, such as floods, earthquakes, wildlife grazing, or wildfires started by lightning. Others are created by people; for example, almost all fires in Sonoma County, livestock grazing, or cutting trees. Ecological resilience is the ability of an ecosystem to recover its functions after a disturbance. Learn more about disturbance in relation to forest stewardship.

- A disturbance may be as small as a tree or group of trees falling over in a forest and creating a sunny canopy gap, or as large as a major wildfire or disease outbreak.

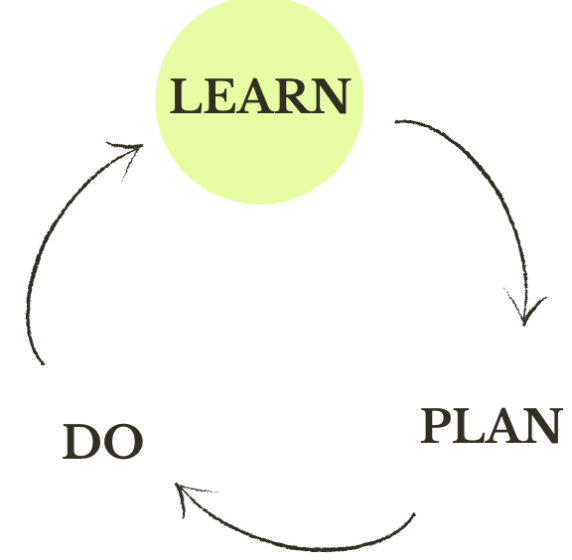

Managing land is not a one and done. It requires ongoing land stewardship. It is about building and retaining a relationship with the land. It can be deeply satisfying.

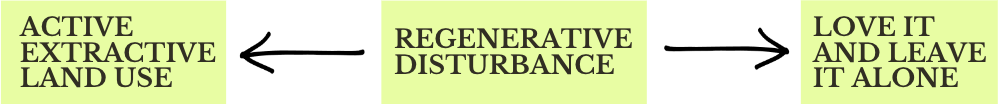

- Disturbance can be beneficial or harmful, sometimes both. Traditional environmentalism says that intervention is bad. Sometimes this is true, but it’s also true that bad outcomes can occur if we do nothing, and good outcomes can occur when we act. One task of land stewardship is to find the sweet spot along that spectrum:

- Indigenous Californians created beneficial disturbance through fire, the cultivation of roots, coppicing stems, weeding, and more. See California Indians and Their Environment, by O. Parrish (Pomo), K. Lightfoot; and Tending the Wild, by M. Kat Anderson.

- Most land in Sonoma County is neither “natural” nor “untouched.” It was tended by Indigenous people for millennia and then over the last 150 to 200 years altered through logging, agriculture, fire suppression, invasive plants, ditching, road building, and climate change, among other factors. Active, informed, and sustained land stewardship is often needed to improve its health and function.

Sonoma County’s ecosystems and species are largely fire-adapted because of millenia of natural and human-caused fires.

Wildfire is one type of disturbance. Wildfire ignitions, wildfire behavior, and wildfire impacts all follow patterns. “Wildfire behavior is controlled by three factors: fuel, weather and topography. (Fuel refers to anything that could burn and spread fire, like trees, shrubs and dried grass.) Therefore, the only practical way to modify fire behavior is by managing its fuel source.” –Sonoma County Regional Parks

Species

- Biodiversity at all levels – microorganisms like fungi and bacteria, arthropods, plants, as well as vertebrates – is important.

- Invasive plant species displace desirable native species that provide food and shelter to wildlife, among other benefits. Invasives from faraway places–such as broom species, Himalayan blackberry, Arundo, several thistle species–often have no local pests or predators. This advantage allows them to push out native species. It requires active efforts to reverse this trend. A few native species like Douglas fir, bay laurel, or coyote brush can become invasive in the absence of beneficial disturbance such as fire or tending by humans. See this video about Douglas fir encroachment.

- Indicator species (for example, steelhead and salmon) tell us about the health of other plants or wildlife, or about the impacts of a stressor, such as drought.

- Keystone species have a bigger impact on ecological processes than would be predicted from their abundance or biomass alone. For example, scrub jays in oak habitats plant millions of acorns every year, increasing oak regeneration beyond what the trees can do on their own. Douglas fir, when it grows in an open woodland, creates deep shade that then prevents sun-loving tree seedlings from sprouting, quickly converting the forest type.

- Ecological engineers (for example, beaver) physically re-shape the habitat they live in, in ways that significantly affect the wildlife.

Source: Ecological Principles for Managing Land Use

Learn to recognize the plant communities on the land, both the native plant species and invasives. Learn the signs of rare species that might live on or pass through your land–black bear, mountain lion, pileated woodpecker, etc. See Land Inventory for more.

Place

- Plant species and their associated animal species are not distributed randomly, but cluster together based on soil, weather, and other factors into typical “associations,” “communities,” “suites,” or “habitats,” each with different dynamics.

- Globally and locally, the major causes of biodiversity loss are the outright loss of functioning natural land, and the fragmentation of land into smaller pieces that support less life.

Physically complex, variable habitats such as “mosaics” support more species. Clumps of plants, downed logs, snags, clearings, patches, edges, and “messiness” are their own microhabitats supporting additional species, as described in Retaining and Creating Habitat Features.

Additional Resources:

Ecological Principles for Managing Land Use

Ecological Concepts, Principles, and Applications to Conservation

The California Naturalist Handbook is an accessible introduction to California’s geology, plants, wildlife, and ecology. It is the text for the California Naturalist course and certification, offered regularly by at least three organizations in Sonoma County.