LEARN

Case Study: Pepperwood Forest Thinning and Burning Project

By Michael Gillogly, Pepperwood Preserve Manager

Large-scale forest thinning projects were launched at Pepperwood in 2007 and have been done every year since. In 2017, this thinning work was paired with beneficial fire (pile burns and broadcast burns) as a way to reduce the fuel loading.

This case study focuses on the 102-acre Weimar Unit with a mix of oak woodlands, Douglas fir forests, chaparral, and mixed hardwoods – with oaks as the dominant species. The unit was manually thinned in September of 2020 with the material from thinning was lop and scattered, and then broadcast burned in October of 2022.

Before we began our forest stewardship work, we defined our goals for the site. These goals are always informed by the data we gather while regularly walking and observing the land. Additionally, we consulted experts—including Pepperwood’s Native Advisory Council, an ecologist, foresters, fire ecologists, researchers, and wildlife specialist—and utilized online tools like the Wildfire Fuel Mapper which allows land stewards and homeowners to download information on vegetation types and other maps for their sites.

Our overarching goals include wildlife-friendly habitat, native plant biodiversity, promoting cultural resources that have been identified by the Native Advisory Council, safe hiking areas, fire resilience, and carbon sequestration in large trees. The approaches we chose to achieve our goals include preparing the site for prescribed fire, removing small Douglas fir trees invading oak woodlands, limbing up dead wood on trees and removing dead shrubs adjacent to trunks to reduce vertical fuel continuity (ladder fuels), promoting hardwood and redwood tree species, and retaining the largest trees whenever possible. Ninety percent of the trees we remove are under ten inches in diameter at breast height.

After we consulted experts and researchers, historical ecologists, Indigenous land stewards and our own observational wisdom, we came up with an approximate number of trees per acre as a goal for optimal tree spacing. This number varies greatly in different ecosystems: for example, a savanna dominated by Blue oaks might have 20 oaks per acre, while an oak woodland dominated by Oregon oaks on a north-facing slope might have 200 trees per acre. On average, we typically use 100-120 trees per acre as a reference point for optimal spacing but don’t get too hung up on that number. We use many factors in determining a thinning prescription.

We prioritized working in areas with Douglas fir trees encroaching into Oak woodlands, using roads and trails that could serve as firelines. This allows us to avoid installing new fire lines for regular broadcast burns. Ridgelines are also important fireline locations. Other considerations include locations to aid in protecting communities from future wildfires, proximity to previously treated land so we are creating a contiguous strategic fire and fuel break, and sudden oak death (SOD) occurrence (some early evidence suggests that heat above 95 degrees Fahrenheit, which we achieve with burning, may kill SOD).

We develop a simple thinning protocol for each treatment site (included below) and review that protocol with the thinning contractor before they begin work. We mark any trees that the thinning crew may have questions about so they can move forward with efficiency. We have a different marking color for trees that need to be cut, retained, or girdled (killed but left standing). We girdle large trees that may damage high-value trees if they were to be felled. Snags (dead, standing trees) provide habitat for wildlife and are less likely to damage large trees after they begin decomposition.

Planning should consider how you will reduce fuel loads–leftover plant and woody material–from the thinning work. Since we were planning to use broadcast burns as a way to reduce the woody slash, our thinning prescription called for a lop-and-scatter method. In areas where large oak trees dominated, we then either removed the flammable material at least four feet away from the trees or used small brush piles to burn off plant material. This allowed us to protect these keystone species from potential damage by high heat. Chipping, mastication, and gully packing are other alternatives. Keep in mind that chipping, mastication, and gully packing are only changing the arrangement of the flammable material and don’t eliminate fuels. Riparian areas along creeks and streams require special consideration and consultation with a professional.

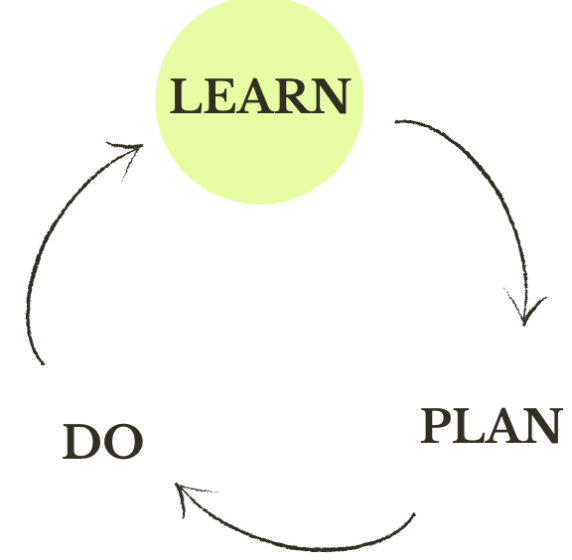

The initial treatments are often the most important and labor intensive but one year of work does not transform a landscape that hasn’t seen stewardship for decades into a healthy ecosystem. All vegetation management activities require long-term maintenance to be successful in meeting your goals. When thoughtfully implemented, the results of thinning and burning projects can help move an overgrown landscape toward a healthy, wildlife-friendly, fire-resilient watershed.

Some areas that might be helpful to investigate, by yourself or with experts, as you generate your thinning plan include:

- What clues exist that tell you what has grown at the site in the past?

- What is the fire history of the site?

- How was the land stewarded in the past?

- Are there trees that appear elongated without many lower branches indicating high tree density?

- What is in the understory (such as dead manzanita skeletons)?

- Is there Douglas fir encroachment?

- Do any tree species exhibit signs of diseases and pests?

- How does the goal of native biodiversity influence your approach? Are there opportunities to add some openings in the forest canopy to allow sunlight in and promote greater diversity and presence of wildlife? How can our actions benefit wildlife, including promoting acorn-bearing oaks, nesting cavities, snags?

- Consider erosion potential in all your actions. Can you place downed trees across the slope to slow water movement?

Forest Thinning Protocol for Oak Woodland and Mixed Hardwood Forests

By Michael Gillogly (Pepperwood Preserve Manager) and Fred Euphrat (Registered Professional Forester, RPF)

Objectives:

- Prepare units for prescribed fire or pile burning.

- Remove small Douglas fir trees to promote oak woodland health.

- Encourage stand recovery of hardwood and redwood tree species given existing species composition.

- Create open stand conditions that reduce vertical fuel continuity (ladder fuels).

- Retain larger well-spaced trees (live or dead) given their existing species composition and size class.

- Retain snags for wildlife habitat.

Thinning protocol:

- Thinning unit perimeter is marked with red flagging

- Retain all living oak, redwood, and pine trees of all size classes.

- Fell live Douglas fir <10” diameter at breast height (DBH). Limb and buck to 36-48” lengths.

- Fell all dead trees <10” DBH. Limb and buck to 36-48” lengths. Keep snags >10” DBH except near trails or roads where they pose a hazard. Red dot means cut.

- Target density and species selection: RPF or Pepperwood staff make these decisions in advance of thinning crew.

- One live tree about every 20’ or one tree per 400 sq. ft.

- To obtain such spacing, remove the worst quality trees. Prioritize to keep redwoods, then pine, then oaks, then madrone, then California bay.

- RPF or staff will be onsite to supervise and assist in determining what trees to keep or remove. Trees over 10” DBH that should be felled are marked with red paint dot.

- Limb downed trees. Buck downed trees <10” DBH to 36-48”. Do not buck previously downed trees >10” DBH to create a more natural appearance. Remaining conifers will be limbed to 8’, hardwoods to 4-6’, with exceptions for large and supporting branches.

- Fell any hazardous tree near a road, trail, fire line or high value infrastructure.

- Girdle red circumference lined Douglas fir trees using double cut method.

- No thinning will occur within 25 feet of a creek (2013 California Forest Practices Rule) except for dead material which will be lopped and scattered. Some exceptions to this rule are possible and would only be considered in consultation with the RPF or Preserve Manager onsite.

- Protect knobcone pine and nutmeg saplings from slash piles giving 36 inch clearance.

- Slash: Lop and scatter limbs and trunks. Clear slash a minimum of 36” from standing live and dead trees. If fuel load is extreme (as determined by RPF or preserve staff) piles will be made to burn prior to or during prescribed burn. Keep piles small (approximately 4 feet in diameter and 4 feet tall). (Note: larger piles may be appropriate, especially in remote areas like Pepperwood, but require special Cal Fire permits. (For more on permits, visit this Burn Pile Guide.) Locate piles away from standing trees as much as possible. Pepperwood staff or RPF will direct the contractor in the field to establish pile locations and size.

- Fire line corridors are marked with green flagging. All dead woody vegetation to be removed from 12 foot flagged corridor. All live vegetation to be removed 6 feet from center of fire line corridor.

- Any vegetation marked with yellow flagging should not be cut.

- Slope and vegetation type may require modification of these protocols.