LEARN: INDIGENOUS LAND GARDENING

Wappo and Pomo Forest Stewardship Practices

By Clint McKay

As told to: Kristina Rizga

Each year, Clint McKay, the Indigenous education coordinator at Pepperwood Preserve, leads several very popular workshops on Indigenous culture and forestry. Considerate, composed, and generous with his knowledge of Wappo culture, McKay enjoys making frequent stops to show visitors soap root, Indian potato, and wild strawberries, all plants which are important to his people and the health of the forest.

Raised in a traditional Wappo and Pomo household, McKay (Wappo, Pomo, Wintun) spent much of his childhood gathering acorns, redbud, and willow needed for basket-weaving. The Indigenous people of California are renowned for the artistry of their baskets, and McKay’s family includes two cultural icons: Works by his late aunts Mabel McKay and Laura Fish Somersal appear in museums and galleries around the world. Both aunts taught McKay the ancient art of basket weaving.

While growing up, every trip to the forest offered McKay a lesson in where each plant chose to live, what it needed to thrive, and how humans could read the plant to understand if the land was out of balance. Plants and animals were considered kin and teachers. McKay’s ancestors observed, for instance, how the acorn woodpecker stored acorns high in dead trees to prevent rotting and attack from insects. Such lessons encouraged Pomo and Wappo people to mimic the strategy by building towering granaries, as McKay describes in his online class, “Black Oaks Revealed.” Observation of thriving forests taught the Pomo and Wappo people the importance of open space between trees. While a densely packed grove of slender oaks might look beautiful to a casual observer, McKay explains, Indigenous people look at trees in terms of their needs and responsibilities toward sustaining the full ecosystem of humans, animals, and other plants. “When oaks grow too close to each other, they are not getting enough sunlight, nutrients, and water,” says McKay. “When oaks don’t have enough breathing room to thrive, they are less resilient to withstand fire, winds and droughts.”

For at least 10,000 years before Europeans arrived, the Indigenous peoples of what is now Sonoma County tended forests and grasslands across huge landscapes to promote biodiversity and prevent destructive wildfires. Small, frequent, and intentional fires were the main practice McKay’s ancestors used to promote biodiversity and reduce the severity of fires. In some forests, they also cut encroaching Douglas firs to increase the number of oaks and madrones that provided food and shelter for wildlife, cultural resources, and building materials. Closer to the ground, weeding, tilling, and irrigating landscapes promoted edible grasses, herbaceous plants, and native vegetables and fruit.

Pepperwood Preserve is a nonprofit research station in eastern Sonoma County that sits on the traditional homeland of the Wappo people. Since 2014, Pepperwood, which is not an Indigenous organization, has worked under the guidance of a Native advisory council chaired by McKay to implement restoration projects that include selective thinning and prescribed and cultural fires. The approach proved itself when the 2017 Tubbs Fire burned 95 percent of the preserve and the 2019 Kincade Fire scorched 60 percent. In the areas that had been thinned and prescriptively burned, few large trees died, and most wildlife soon returned and thrived. Since then, Pepperwood has become a model for how combining science with local Indigenous research, knowledge, and practices can restore forest health and resiliency while mitigating the growing frequency and severity of fires.

McKay brings Indigenous perspectives to nearly every aspect of Pepperwood’s programming: research, thinning and native plant uses, public education, and making Pepperwood more welcoming to Native people. In 2022, for the first time in over 100 years, the council returned cultural burns to Pepperwood. Currently, their focus is on repopulating the land with more of the edible and medicinal native plants essential to sustaining Wappo culture.

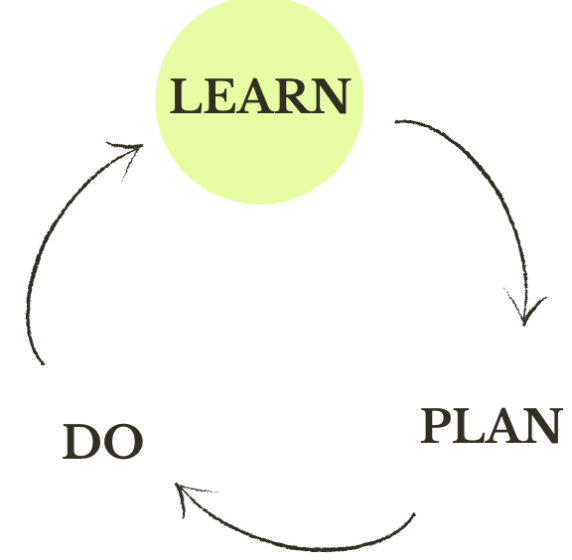

“My people cared for every part of this forest, but living with the land is different than managing it,” McKay explained during a recent guided hike in 2022. “I don’t believe we have the right to control nature. We work with it from a place of responsibility, respect, and reciprocity. This means that every time we do something in the forest, we ask, ‘What is in the best interest of animals, plants, soil, water, air, and humans?’ Humans are in that circle, but we are just one of the spokes in the wheel.”

This excerpt was adopted with permission of Clint McKay and Kristina Rizga from “Learning How to Garden a Forest,” published in Grist.

Clint McKay is a Native speaker of the Wappo language as well as some Pomo and is a culture bearer with extensive Native historical knowledge, not only of Pepperwood but also of the entire region. McKay is a born naturalist with a deep understanding of plant communities and traditional Wappo methods of nurturing them. He is a gifted basket weaver and he serves on the Board of the California Indian Basket Weavers Association. McKay is also a traditional Wappo spiritual leader and the headman of a traditional dance group. McKay has a Master’s Degree in Indigenous Education.

Additional Resources:

To sign up for McKay’s guided hikes on Indigenous culture and forestry, visit Pepperwood’s classes and events page or sign up for their newsletter.

Online class with Clint McKay: “Black Oaks Revealed: Their Cultural Significance for Indigenous Communities,” produced by Pepperwood Preserve, 2021.

In this 2023 video, “Steps to Land Back: Native Advisory Councils,” produced by Redbud Resource Group, McKay shares his thoughts on how to work directly with Indigenous community members to create meaningful co-stewardship of parks and preserves.

In this 2019 video McKay discussed the art and craft of Pomo and Wappo basket weaving. The video includes photographs of unique baskets from the McKay family’s private collection.

McKay co-authored the 2022 study, “Examining abiotic and biotic factors influencing specimen black oaks (Quercus kelloggii) in northern California to reimplement traditional ecological knowledge and promote ecosystem resilience post-wildfire.”