DO THE WORK

Limbing Up Trees

Limbing consists of removing the lower branches of trees or shrubs, to lower the risk of fire reaching the upper branches.

Benefits

This practice reduces wildfire intensity by removing ladder fuels. Increasing the distance between surface fuels and the lowest branches on a tree reduces the chance that fire on the ground will climb into the tree’s canopy to create a crown fire. This benefit is especially important along roads, so that firefighters and residents can get in and out during a fire.

Crown fires are intense and fast-moving… virtually unstoppable, and often result in large burned areas despite costly and dangerous fire suppression efforts.” – United States Forest Service

When & Where to Limb Up Trees

Primarily, limbing is used in shaded fuel breaks, thinning, along roads, and in the defensible space around structures, particularly where trees are dense. Limbing is done where lower limbs create problematic fire ladder conditions, in particular species such as pines, Douglas fir, or redwood, where the lower limbs naturally tend to die and become flammable.

Larger chaparral species, such as manzanitas and toyon, naturally have multiple large limbs or trunk originating from the same place, so limb with a lighter touch in these areas.

Limbing is closely related to the practice of Thinning and both techniques are often used together to increase fire resiliency. After fire or clear-cutting, trees tend to regrow with a multitude of new stems and branches, and it is often advisable to thin and limb the regrowth to two or three of the healthiest stems.

Photo Credit: US Forest Service.

Key Points Before Proceeding

Without proper technique, cuts to trees can lead to improper healing, disease, and the death of the tree. Cutting too many limbs from a live tree can kill the tree. Learn proper cutting technique, and get training or guidance from a professional arborist or forester.

Limbing up oaks is not usually necessary from a fuels management standpoint, since the trees are not highly flammable, and given their growth habit they can be damaged and unbalanced by limbing.

“Separate the ground from the crown” – Brock Dolman, Occidental Arts and Ecology Center

How to Limb Up Trees

Generally, remove branches at least six feet from the ground. On smaller trees, limb up only to a height of ⅓ of the tree’s total height. Removing more than ⅔ of the vertical height of a tree’s live branches harms the tree and reduces its lifespan.

Unless necessary, only remove branches that are small enough to cut with hand tools. Larger branches are far less flammable. Their removal is more likely to harm the tree and is more dangerous to the person cutting.

Here’s a paraphrase of US Forest Service guidelines on which branches to cut:

- Less than 2 inches diameter – go ahead

- 2-5 inches diameter – think twice

- More than 5 inches diameter – have a good reason

Professionals often choose not to limb up certain desirable species, such as oaks; or madrones and buckeyes; or hardwoods generally. They are less likely to burn, and they contribute to habitat and biodiversity. You may want to have different rules for different species, always keeping in mind the type of forest you are aiming to create.

Avoid damaging trees by using proper cutting technique. See below or this link for more information.

The upper branches that are exposed after lower branches are removed will occasionally droop downward over time, consider limbing up a bit higher if it’s critical to maintain empty space under a given trees.

Branches growing parallel to the ground can be retained for ecological or aesthetic reasons, especially if they are large in diameter and therefore less flammable. In situations like these it’s important to consider your values, risk tolerance, and potential benefits.

Variations on this Practice

To retain understory vegetation for ecological or aesthetic reasons, you can increase fire resilience by separating the trees and understory vegetation so that the lowest branches on the trees are three times the height of the understory vegetation. This is a good way to balance ecological, aesthetic, and safety values.

Illustration: Ellie Insley.

In specific locations where emergency vehicles might need access under the trees, limb up enough to allow their clearance. For most fire vehicles 12 feet is acceptable.

Timing Considerations

Limbing is best done when trees are dormant, generally in the winter months. Some species, such as coast live oak, operate on different schedules.

Avoid limbing up during bird nesting season, generally from March through August in Sonoma County. This timeframe covers nesting season for the majority of songbirds and raptors (birds of prey). If vegetation management must be done during nesting season, see Nesting Bird Surveys. Surveying over a longer period can protect more types of birds. For example, the Northern Spotted Owl can begin nesting as early as January in Sonoma County.

If you must use gas-powered tools do so before the day heats up, and on still days (days with little or no wind), to prevent starting fires. Take precautions such as having water and a shovel at hand, not setting hot tools on the ground, and avoiding contact with flammable materials.

Avoid working when the soil is wet, in order to avoid churning up soil and causing erosion.

Equipment

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

- Long pants

- Long sleeve shirt

- Boots

- Helmet

- Eye protection

- Leather gloves

- Ear protection if using power tools

Tools

- Hand saw

- Pruner and/or loppers

- Pole saw or a ladder to use with hand tools

- Chainsaw or mechanical pole saw (different tools are useful for different branch sizes)

Local steward Mike Stern limbs a Douglas fir for fire resilience in West County.

Maintenance

Check your limbed trees every two to three years. Juvenile trees need more frequent attention than mature trees. Inspect after heavy wind or winter storms to see if any trees have been damaged or need additional pruning.

Related Practices

Retaining & Creating Habitat Features

Please note: this is a general guide. The specifics of how and when to do this practice will depend on many factors, including the site’s particular vegetation, climate and topography, history, and land management goals. Always consult with a professional if you’re unsure.

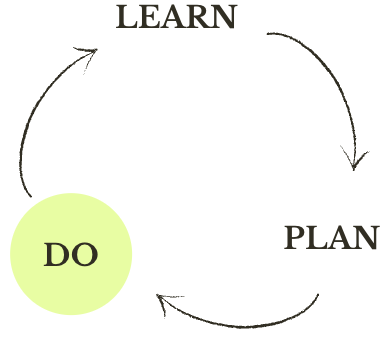

Do you have your principles in mind? Remember to regularly check in with your land management goals, to assure your practices and actions will actually achieve them.