Thinning is the selective removal of tree or shrub trunks that are growing directly from the ground. Thinning can be accomplished by cutting or girdling; it can focus on one species or many. (In contrast, limbing removes only branches from a tree.)

Cutting is easy, managing the wood is the tricky part.

The foreground of this photo from Pepperwood Preserve shows an oak woodland that has been thinned to release the oaks and reduce the risk of high-severity crown fire, and in the background an area not yet thinned, crowded with Douglas fir that has grown into (“encroached upon”) the oak woodland.

People use the word “thinning” to cover a range of approaches, including:

- Thinning for ecological health or forest restoration eases competition among plants and can create “mosaics” – patches of large trees interspersed with diverse shrubs and herbaceous plants.

- Thinning for wildfire resilience or fuel reduction (possibly as part of a shaded fuel break or before using beneficial fire) reduces the volume and connectivity of flammable material. Thinning in the defensible space has specialized guidelines; see, for example, Resilient Landscapes for guidance tailored for Sonoma County.

*In order to avoid putting the trees you value at risk, it is critical to have a plan for Managing Woody Material in place before you begin thinning.

To achieve either objective, thinning should focus on removing the smaller or unhealthy plants and retaining the largest, healthiest trees. For example, removing Douglas firs that are encroaching into oak woodlands is a common example of thinning. (See chapter on Managing Woody Species Encroachment.) Selective thinning can also be used as part of timber management and sale.

The word “clearing” should be avoided since removing all plants is typically not an effective way to achieve common land stewardship objectives.

Benefits

Thinning, when combined with an appropriate strategy of handling cut plant material (see chapters on Managing Woody Material, Beneficial Fire, and Pile Burning), can reduce the risk of high-severity wildfire by separating fuels and live trees, which in turn reduces the temperature and severity of subsequent fire so it doesn’t kill desired plants or escape control lines. Overly dense forests can lead to catastrophic wildfires which are more likely to damage the mature trees we value and can make tree regeneration difficult.

Specialized thinning along roads (see Shaded Fuel Breaks) makes emergency access roads safer for firefighters and residents. Once regular beneficial fire is returned to the land, manual or mechanical thinning can be greatly reduced or may no longer be necessary.

Thinning can be beneficial if there are signs of overcrowding or poor health. Giving plants room to grow to their full potential and mature size creates forest health. Appropriate thinning promotes vigor among the remaining plants, increases their size and resilience to droughts, wildfires, pests and diseases, promotes greater seed production, and increases overall ecosystem health. Vegetation communities with optimal spacing compete less for resources such as light, water, nutrients, and fresh air. When plants are less crowded, more moisture is retained in plants and soil later into the dry season, reducing flammability. Some plant pathogens such as Sudden Oak Death rely on wet conditions and are less transmittable when air circulation is strong.

Thinning for forest health creates beneficial “mosaics” of denser and less dense areas. These foster diverse habitats by increasing light at the forest floor, which in turn promotes a variety of plants that can be used for shelter and forage for animals. Mosaics can also reduce severity and size of fire; because openings in the landscape have less fuel, a wildfire traveling through areas of mixed vegetation tends to be less severe.

Plants are mostly carbon, so thinning affects carbon storage and sequestration. Globally, this matters enormously, because excess carbon and other gasses in our atmosphere are cooking our planet. But it’s complicated; see Carbon in Your Goals for more information.

Thinning can increase the amount of water in the soil or in local streams, at least for some period of time, because thinning reduces the number of trees competing for water.

Thinning makes it easier for both humans and animals to move through natural areas. Thinning is done differently depending on land management goals. When setting goals, expert guidance from an arborist, forester, ecologist, Indigenous practitioner, or land management professional is highly recommended. (See Resources for Implementing.) A common rule of thumb is that trees larger than 11 inches in diameter (measured at breast height) are more appropriate for professionals to handle.

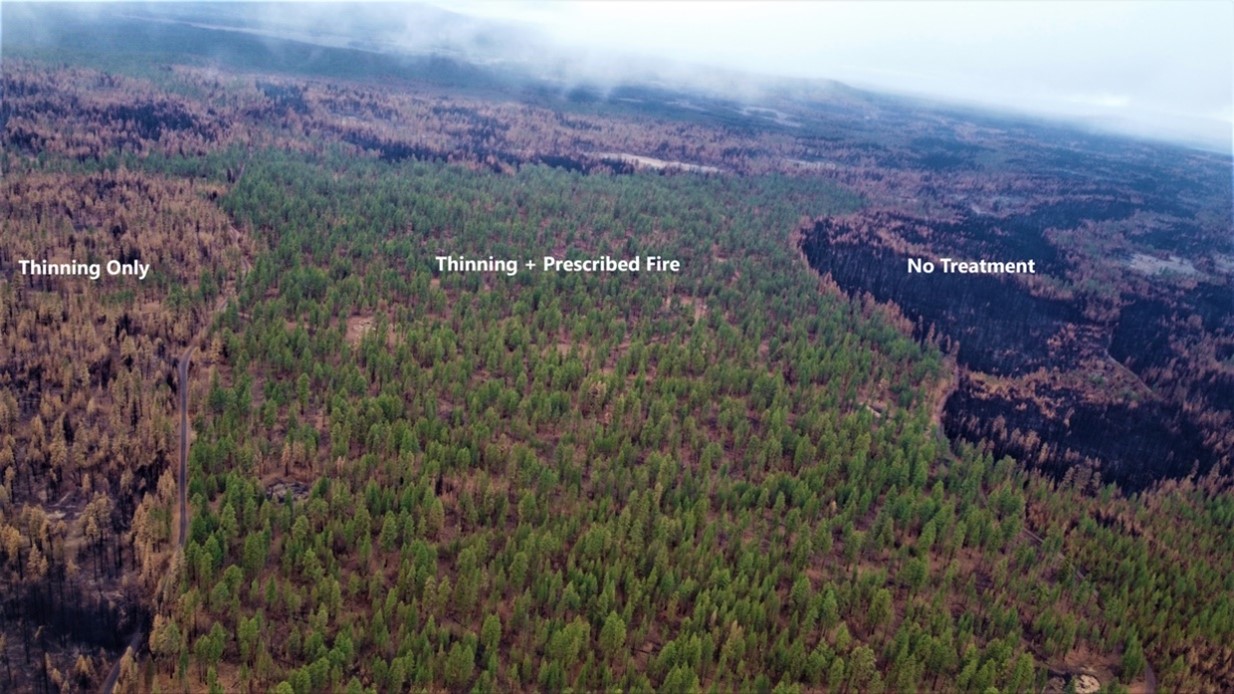

Thinning combined with Limbing, Managing Woody Materials, and Beneficial Fire can produce dramatic results. This aerial photography shows how different treatments moderated the impact of Oregon’s 2021 Bootleg Wildfire.

Background

For at least 10,000 years prior to European contact, Indigenous peoples of what is now California tended the land with thinning and fire. Their complex and sophisticated land stewardship practices promoted biodiversity and reduced the severity of fires.

Fire suppression and exclusion of Indigenous stewardship from the land, among other factors, have substantially changed the composition of Sonoma County’s woodlands in the last 200 years. A 2023 study found that in some parts of the county, the extent of Douglas fir forest has increased between ten to 80 times. Many scientists find overcrowding throughout the West and link these changes to hotter and larger wildfires. One study found that severe fires, in which a conflagration kills 75 to 100 percent of the trees, are larger and occur more frequently in California than at any time in recorded history.

When and Where to Thin

Thinning is called for where the stems, trunks or resprouts of woody species are too close together to allow the plants to grow to their full size, or when they create high-severity wildfire conditions such as contiguous flammable material (i.e. an oak woodland where Douglas Firs are encroaching).

Thinning can be beneficial if there are signs of overcrowding or poor health, including:

- Only 30 percent or less of a tree’s crown is alive,

- The area has many dead trees,

- The shapes of trees are much different (usually skinnier) than a free-growing tree of the same species,

- The tree and shrub density makes travel for wildlife such as deer or bear difficult.

Thinning is called for in many vegetation communities (such as mixed conifer stands, oak woodlands, mixed hardwood forests, or chaparral) that have not been thinned, limbed, or burned for ecological or fire resiliency goals in the recent past. (Approximately, “the recent past” means the number of years in that vegetation community’s pre-European fire return interval).

There are exceptions: some less-common vegetation types, such as Bishop pine or Sargent cypress forests, do not reproduce except after high-severity, stand-replacing fire, and they naturally grow in very dense same-age stands. While there may be other reasons to thin such stands, it is unnecessary for forest health.

Vegetation management including thinning when combined with Beneficial fire can reduce the severity of subsequent wildfire. The right side of the photo is an area burned intentionally in 2019 at Monan’s Rill in northeastern Sonoma County. Surface fuels were consumed by the burn. The left side has just burned in the 2020 Glass Fire. The Glass Fire stopped at the edge of the prescribed burn, because there was not enough fuel to carry it. Photo: Chris Schaefer.

Key Points Before Proceeding

Photo and caption from UCANR Forest Vegetation Management.

Thinning larger trees is dangerous. Trees are heavy, the direction of their fall is hard to predict, and power tools are dangerous. A common rule of thumb is that felling trees greater than 11 inches in diameter at breast height (dbh) is best handled by professionals.

A forest can be thinned too much, in which case decades worth of growth and ecosystem services (the benefits that ecosystems offer humans, such as clean air or water) can be lost. More thinning is not better; thin the least amount that will accomplish your goals.

The optimal spacing of trees (which can also be described in terms of trees or stems per acre) depends on plant species, site conditions like sun exposure and soil type, fire history, and tree age, among other factors. For example:

- If an area was burned or cleared recently and the only trees are young and/or small, then 10 to 15 feet between tree saplings may be appropriate.

- The density of Redwood forests can be drastically different dependent on a wide array of site specific variables. Some examples of densities in healthy stands are: 250 trees per acre for second-growth stands, 74 trees per acre at Armstrong Redwoods State Park, and 53 trees per acre at Humboldt Redwoods State Park (the average spacing from the center of one tree to the center of the next at these sites is 26 feet, 48 feet, and 57 feet respectively). Please note that the final two numbers include only trees over 6 inches in diameter at breast height.

Study these photos for examples of tree spacing before and after thinning.

Preparing for thinning follows the same thought process regardless of whether you will do your own work or hire contractors:

- Thinning begins with deciding which trees to retain, and marking the trees you want to remove to achieve your land management goals. For example, if promoting wildlife is important, you will retain more unique, damaged, and some dead, standing trees (snags), because they provide increased habitat for animals and insects. Consider retaining trees with unique structures and trees with multiple trunks that can often grow together, limbs leaning on other limbs, snags, or dead tops–as these can offer great habitat for animals.

- Generally, thinning for any purpose should retain the largest and healthiest trees and shrubs. Large, healthy trees are typically most fire resilient and provide the most ecosystem services, such as clean air, habitat, or carbon sequestration. If cut, it could take decades or centuries to recover or replace the services a mature tree provides.

- Consider favoring oak trees for retention, if your site has them. Ecologists consider oak trees keystone species, because they provide more food and shelter to animals and insects than any other tree. (See Retention and Creation of Habitat Features to learn more.) Evergreen oak species like coast live oak cast dense shade all winter, quite different from deciduous oak species, which may affect your priorities.

- Consider retaining fruit-and nut-bearing plants such as oaks, madrones, bay laurels and manzanitas, among others, because they provide food for wildlife and cultural resources for people. This is the practice of many Indigenous communities in California.

- As a forest or shrubland ages, the plants need to get bigger, so the spacing needs to increase. Visualize the full extent of the canopy of the longest-lived trees or shrubs on your site, at maturity, to help understand the ultimate stem density your site could attain. If plants are crowding or over-topping your desired retained trees or shrubs, consider removing them. For instance, California bay trees over-topping oaks or other hardwoods can be removed to reduce Sudden Oak Death (which they carry) and bring in more light.

- The spacing you create between larger shrubs or trees should not be uniform. Variety in the height, spacing, density, and species of plants promotes biodiversity and reduces the severity of wildfires. Storms, fire, grazers and browsers, disease, and other disturbances help bring variation to individual trees and the overall spacing of the forest. See practice Retention and Creation of Habitat Features.

- It’s best to plan multiple rounds of modest thinning, over years, instead of fewer rounds of extreme thinning. Gradual thinning over time means that more canopy cover is retained at all times. The benefit of greater canopy cover is that the canopy casts shade that inhibits the growth of flammable non-native grasses, thistles, and brooms. Retained trees will gradually expand their canopies after thinning.

Thinning produces a large volume of woody material. On many sites, the thinning process can take less effort than the subsequent disposition. Before you begin, you need a strategy for handling cut plant material. See chapters on Managing Woody Material, Beneficial Fire, and Pile Burning.

Example of grassland, savannah, and oak woodland intergrading with each other in irregular patterns and indistinct edges. Eastern foothills of Sonoma Mountain. Photo: Sonoma Ecology Center.

Generally, thinning on public land, or using public funds, requires permits, and thinning on private land does not. Some types of thinning require in-depth planning and a permitting process such as a California Vegetation Treatment Plan (Cal-VTP) or, if harvesting trees for sale, a Timber Harvest Plan (THP). Some permits require working with a Registered Professional Forester (see Permitting and Compliance). People stewarding land in Sonoma County can often get a free consultation with a local UC extension advisor or a Resource Conservation District advisor. See Resources for Implementing.

How to Thin

Decisions on which trees to leave and remove are among the most important in forest stewardship. Consulting a professional is highly recommended. See Resources for Implementing.

Planning Considerations

Here is an example sequence of work that will vary depending on whether you are doing your own work or hiring contractors:

- Using tape of varying colors, mark trees and shrubs that will be retained, where openings will be located, or dense patches to be retained for wildlife habitat. On trees or shrubs with many stems, where the stems are much smaller than their mature size, decide and mark how many and which stems to retain. Mark any keep-out areas that are off-limits to disturbance. Be sure to read Retention and Creation of Habitat Features so you retain the most important wildlife features. See also these tips on the art and science of marking trees.

- Decide where and how cut material will be collected or dispersed (see chapters on Managing Woody Material, Beneficial Fire, and Pile Burning), and the routes by which it will be moved.

- Based on all the considerations in this practice, write down general rules (sometimes called prescriptions or treatments) to apply outside the above special areas, such as “remove all stems/trunks less than X inches dbh (diameter at breast height)” or “leave X feet between remaining large trees.” These general rules will change based on conditions and objectives. For example, you may remove more stems along a road or trail (see practice Shaded Fuel Breaks) but fewer in most of the treatment area (see practice Optimizing Forest Health-coming soon).

- If you are working with a hired crew or volunteers, distribute these written rules and priorities to each team member, walk around with them to fine-tune their approach as they begin the work, and observe their work frequently to ensure things are proceeding as you expect.

- Begin implementing your plan, either on your own if you have the skills, or with competent contractors.

Variations on this Practice

The answer for tree and shrub spacing is often “it depends;” different rules and spacings should be used as conditions and goals shift.

For example, if promoting biodiversity is a high priority, small or young trees may be kept if the distribution of their species is limited or they are the only examples of their species in an area.

Another example: The outermost trees in a stand often develop stronger wood to sustain wind forces and shield trees further into the stand from high winds. When trees that are shielding the stand from the wind are removed, a changed dynamic of wind exposure can create undesired effects. If thinning may expose trees that are otherwise protected from high winds, consider consulting with a Registered Professional Forester or certified arborist to “feather” or lighten your approach along the stand edge.

Photos: Will Spangler.

PG&E removed a swath of 100+ year old conifers in the powerline right-of-way. The remaining trees were exposed to wind forces they were not accustomed to, creating a domino effect that brought down over 15 mature trees.

An example of whole tree failure from a 2023 wind storm in West Sonoma County.

Timing Considerations

Thinning is best done after bird nesting season, generally from March through August in Sonoma County. This timeframe covers nesting season for the majority of songbirds and raptors (birds of prey). If vegetation management must be done during nesting season, consider suggestions in the Nesting Bird Surveys chapter.

Equipment

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

- Long pants

- Long sleeve shirt

- Chaps

- Boots

- Helmet

- Leather gloves

- Eye and ear protection

Tools

- Hand saw

- Pruner and/or loppers

- Pole saw or a ladder to use with hand tools on smaller pieces

- Chainsaw

- Mechanized pole saw

- Peaveys , rock bars, or other tools for moving large diameter or heavy wood

Maintenance

Thinning is often ongoing, unless beneficial fire or another low to moderate intensity disturbance such as targeted grazing can be introduced and repeated regularly. A site with favorable growing conditions (plentiful water, ideal sunlight, rich soil) will need more frequent maintenance.

Once cut, many woody species, other than conifers such as Douglas fir, are likely to resprout. How resprouts are managed is defined by the intended outcome: Do you want this plant in this location?

- If no, then remove all resprouts. Where manual or mechanical maintenance is not feasible, for very vigorous woody resprouters like eucalyptus, acacia, mature broom, or California bay, you may consider dabbing a small amount of herbicide on fresh-cut stumps, without causing wider harm.

- If yes (the plant is acceptable in that location(, then ask…

- Do dense resprouts pose a problem or risk for this particular location and warrant thinning?

- If no, then no action is needed.

- If yes, then for trees remove all but 2 or 3 of the tallest or most vigorous sprouts to accelerate upward growth. For shrubs, generally retaining all resprouts is fine.

- Do dense resprouts pose a problem or risk for this particular location and warrant thinning?

Related Practices

Retaining & Creating Habitat Features

Managing Roads and Trails (coming soon)

Please note: this is a general guide. The specifics of how and when to do this practice will depend on many factors, including the site’s particular vegetation, climate and topography, history, and land management goals. Always consult with a professional if you’re unsure.

Do you have your principles in mind? Remember to regularly check in with your land management goals, to assure your practices and actions will actually achieve your goals.

Additional Resources

Unfortunately, there are few peer-reviewed studies on the effects of thinning in the vegetation communities of Sonoma County. Most of the resources listed are from similar ecosystems across California and the West.

Lessons learned from Pepperwood’s thinning and pile burning (see pages 86-89).

The Art of Marking [Trees] and a sample prescription for achieving both wildfire resilience and increased biodiversity goals.

For a thorough discussion of various forest thinning goals and methods, visit Forest Vegetation Management chapter in UCANR’s Forest Stewardship Series.

California’s two-decade The Fire and Fire Surrogate Study evaluated the effectiveness of various forest treatments, including thinning.

Adapting western North American forests to climate change and wildfires: 10 common questions summarizes research on forest treatments, including thinning.

Ecological Thinning Guidelines‘ from fire-adopted landscapes in Australia are an accessible review of key principles of thinning and ways to minimize negative effects.

California Indians and Their Environment and Tending the Wild are groundbreaking books documenting forest stewardship practices by the Indigenous people of what is now California.

Informational video with Clint McKay (Wappo, Pomo, Wintun): “Black Oaks Revealed: Their Cultural Significance for Indigenous Communities.”

This story reviews the latest research on the benefits of ecological thinning: “Learning How to Garden a Forest.”

This one fact will completely change how you think about California wildfires, by the San Francisco Chronicle, has excellent illustrations on what California’s forests looked like before and after fire suppression policies and explains how thinning and burning can reverse these changes.

These maps from the San Francisco Chronicle track forest treatments, including thinning and prescribed fires, for the decade leading up to the 2021 Caldor Fire.